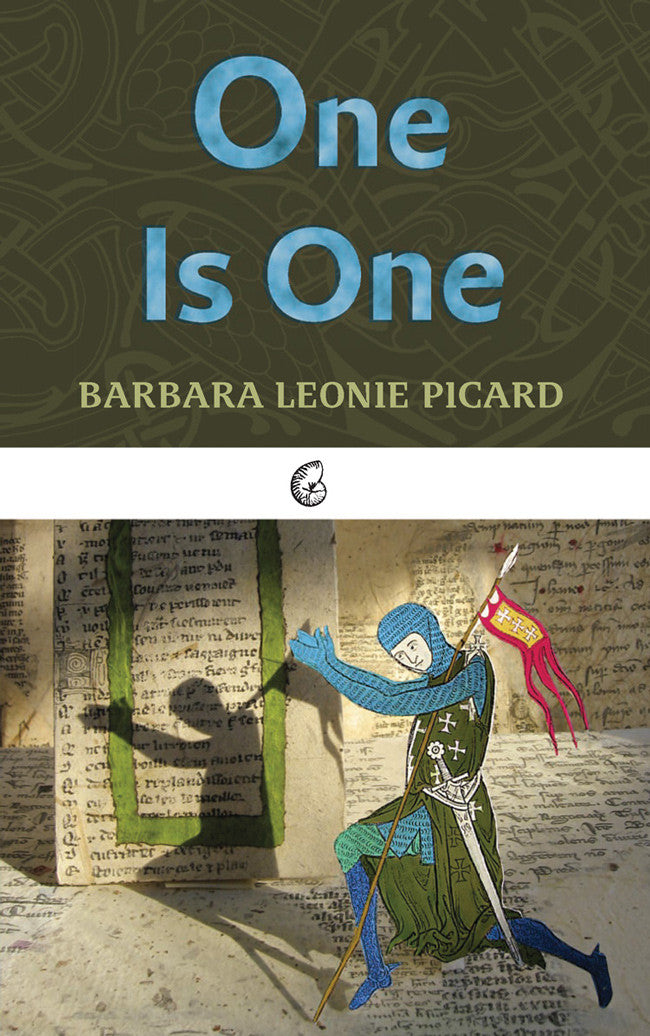

One Is One

One Is One

Barbara Leonie Picard

Couldn't load pickup availability

285-page paperback / 5" x 8" / ISBN 978-1-58988-027-6 / Publication Date: July 2006

In 14th-century England, Stephen de Beauville dreams of becoming a knight—not a promising ambition for a contemplative boy with a talent for drawing. Quiet and solitary, Stephen must endure the bitter torments of his brothers and cousins until he finds his first true friend; through that friendship Stephen gains courage to endure the lack of kindness in his life. But believing that Stephen will never possess the valor to be a knight, his father abruptly sends him away to spend the rest of his life in a monastery.

After a harsh apprenticeship in the monastery, Stephen realizes he must flee its confines. In a twist of fortune, he becomes squire to a wise knight and then attains knighthood himself. The death of his own young squire causes the twenty-six-year-old Stephen to re-examine his ambitions. In doing so, he makes an important discovery: His journey through dangerous times has instilled in him the strength and self-confidence to find his true place in the world. One is One portrays a man ready to heed his mentor's maxim: "Do not be afraid to do what you want to do."

Several of Barbara Leonie Picard’s many books, including One Is One, have been shortlisted for the Carnegie Medal, Britain’s oldest children’s book award.

"Her narratives have the ring of tales told by skald and bard, and her choice of words would fill great halls. Her literary fairy tales are lushly romantic, with poetic language and an almost other-worldly knowledge that informs and enriches them. Open one of her books and read it aloud. See how her words will still echo in the storytelling rooms and libraries that have become our great halls." —Janice M. Del Negro

"In One is One . . . there is a large cast of entirely credible characters and a good contrast is pointed between fourteenth-century courtly and monastic life. The strength of this book derives from its concern with important themes—loneliness, loyalty, courage and love; above all, self-knowledge." —The Spectator

"Miss Picard has been bold in choosing for her hero a weakling and a coward. The final resolution of Stephen's doubts, though not unexpected, is most beautifully handled." —Times Literary Supplement

Barbara Leonie Picard (1917–2011) was the author of over twenty-five books, all of which have received praise for the mature and thought-provoking fare they offer young readers. Her first book was published in 1949. Her works include five historical novels for young adults, many retellings of myths and epics—including the Odyssey and the Iliad, the story of King Arthur, and legends of the Norse gods—and collections of fairy tales. Several of her books have been shortlisted for the Carnegie Medal, the oldest children's book award in the UK. Paul Dry Books also publishes Picard's book Ransom for a Knight.

From "Something about the Author Series, Volume 10" by Barbara Leonie Picard:

I have never written with children or, indeed, anyone else in mind, but always for myself. I have accepted only commissions which I wanted to write, and refused all others. I have published for money—how many writers have not? We have to eat, after all—but I have never written for money: there is a difference. Any story I have written has been a story I would have wanted to read myself. Indeed, sometimes when there is no other book to hand, I can take up one of my own and read—and even enjoy—it, as though it had been the work of someone else. This probably sounds narcissistic and excessively conceited, but I believe that it is not. There seems to me to be no reason in the world why a story written for one’s own enjoyment should not be read for one’s own enjoyment. [Walter de la Mare once wrote: "Indeed every writer who is notmerely writing books in order to sell them, or in order to teach, to instruct, to edify, or solely to pass the time away… every such writer is writing not only for, but even to himself."] Of course, reading what one has written years before is not unalloyed pleasure. Too often one finds oneself wincing at a word and thinking, "That is wrong, it should be so-and-so," or pausing at a clumsy phrase and saying, "I would know better than to put it that way now." Yet, in spite of all such self-criticism, I am able to enjoy reading my own books. If others also should have enjoyed them, this, as it were by-product, can only be for me a bonus, and I am truly glad of any little pleasure I may have given to anyone else. But I can honestly say that, in all my career, the words of this article which you are now reading are the very first which I have written, not for myself, but for others.