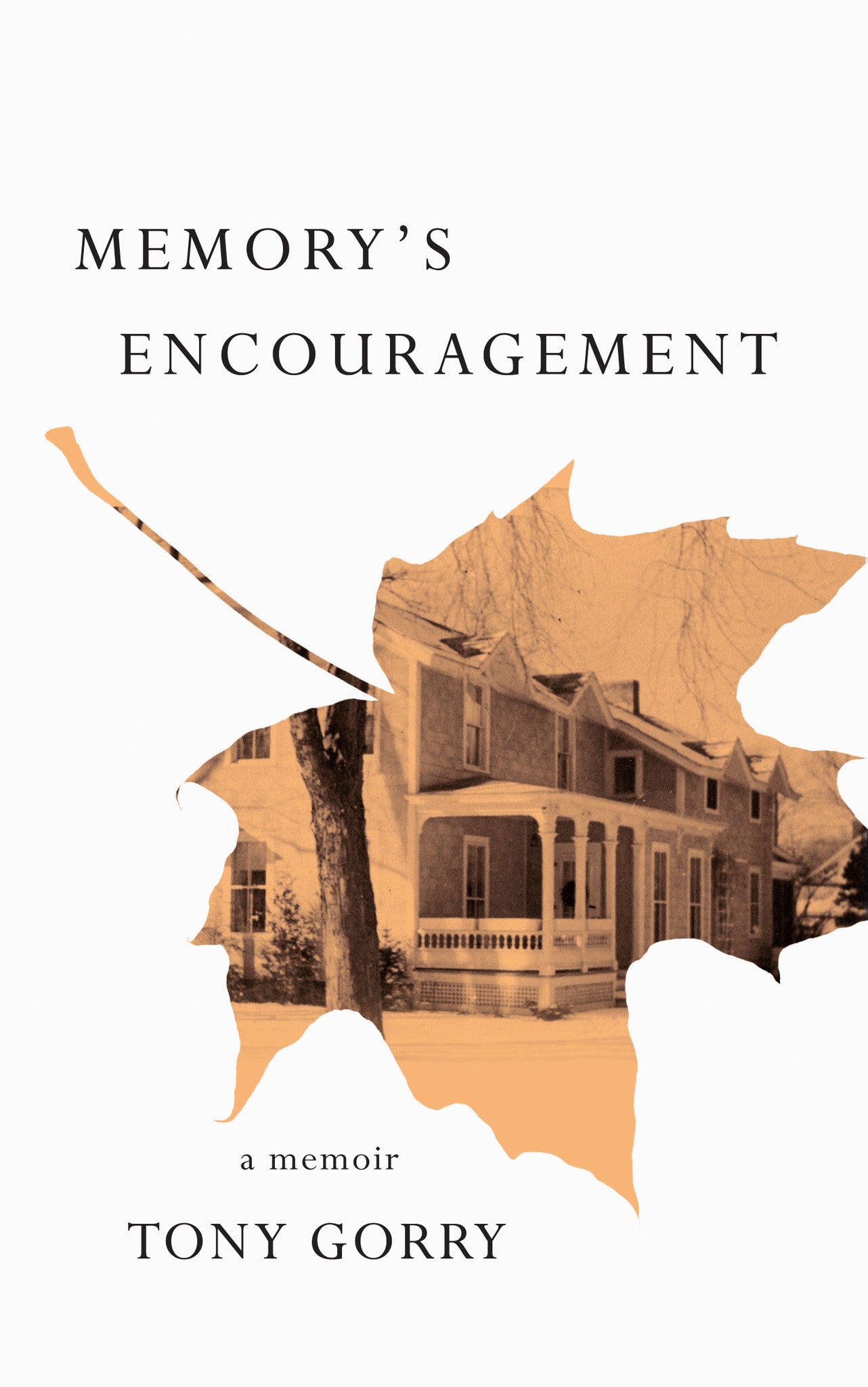

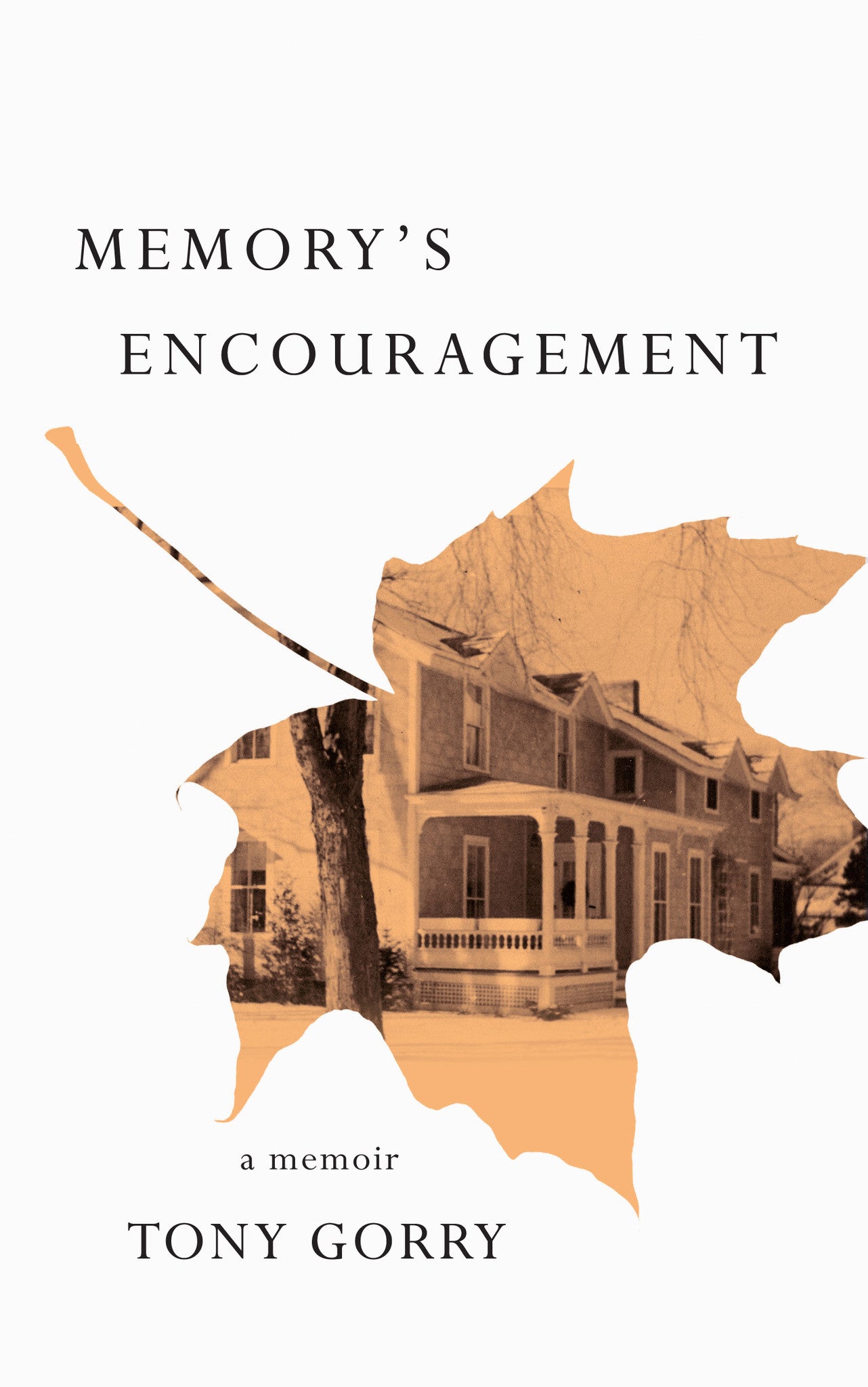

Memory's Encouragement

Memory's Encouragement

Tony Gorry

Couldn't load pickup availability

On Language, Memory, and Illness / 262-page paperback / 5" x 8" / ISBN 978-1-58988-121-1 / Publication Date: 4/18/2017

As Tony Gorry recalls scenes from his earliest childhood and adolescence, he weaves his present reality with these images to unlock meaning hidden in the remembered moments. On their surface they may appear “ordinary,” but as Memory’s Encouragement reveals, they point the way to a life well lived. Gorry also “remembers” events at which he was never present: the evening his parents first met, his father’s World War II experiences. He explores these recollections—not really memory at all—and finds them as important to the way he understands his life as those he actually lived through.

At the center of Memory’s Encouragement, Gorry writes about his decision to study Greek in his late sixties; he wanted to read Homer in the original. As he began to learn the ancient language, Gorry, one of the first PhDs in Computer Science from MIT, also came to realize that he was going to have to slow down in order to learn well.

With careful introspection about his past and courage in the face of his current cancer treatment, Gorry offers a compelling narrative about how to discover significance in one’s life.

"A wonderful book, poignant and profound, that evokes the era of Gorry’s childhood — the 1940s and ‘50s — in Glens Falls and explores in a surprisingly gritty and clear-eyed fashion the emotional dynamics of his family that shaped his life."

—The Post-Star

G. Anthony Gorry is the Friedkin Professor Emeritus of Management at Rice University. He is a member of the National Academy of Medicine and a Fellow of the American College of Medical Informatics.

Also available as an ebook:

- Amazon

- Apple iTunes Bookstore

- Barnes & Noble

- Google Play

- Kobo (See IndieBound's list of independent booksellers selling e-books.)

An excerpt from "The Ice House"

It’s a late summer afternoon in 1945. A male deer is leading two females along a switchback on the side of Buck Mountain in the Adirondacks in upstate New York. They’re halfway across the last turn when the sharp crack of a rifle splits the air. The buck stops abruptly, standing rigidly in the soft light. The does freeze as well. For some moments, only his ears and nostrils move. Then he shakes himself, sending a ripple under his coat from his neck to his haunches. He snorts, and turns from the trail onto a narrow rocky track hidden by bushes. The inner side of the path clings to the mountain, but the outer edge drops off sharply to the valley below. The buck and his companions clatter out along the ridge. As they round a bend, the buck again stops. Standing still, he surveys the vista of the lake laid out below. The females fidget, awaiting his direction. Twenty seconds later, he snorts once more and starts up again. The three deer round the bend and are soon gone.

As the second doe makes the final turn, one of her back hooves dislodges a small rock, sending it spinning over the edge of the trail to carom down the hill. It flickers as the fading light catches a polished side. The rock glances off a large boulder and spins sharply off course. It bounces twice, once left, once right, into a patch of moss-covered stones. It strikes the edge of a large tree root, seems to poise for a moment, and finally nestles into a depression among mottled leaves.

Below the deer, between the mountain and the lake, lies the Knob, a loose cluster of summer cottages and permanent homes, sited on an abutment into Lake George. Only a few hardy souls live in the Knob during the region’s harsh winters, but in summer, the cottages are filled with families drawn by the swimming, boating, hiking, and sheer beauty of the lake. During the war years it is mostly mothers who bring their children, seeking a few days break from work and from loneliness and fear for their husbands overseas.

The Ice House is the gravitational center of the Knob. Flanked by boat slips and a gas station, it stands by the packed dirt road that edges the lake. It’s festooned with hand-painted signs, proclaiming “Beer, Pop, and Pinball” and “Honest Weights and Square Trade.” During winter, workers with pick axes and ripsaws cut out blocks of snowy ice from the lake and pack them in a windowless cellar in back. Covered with burlap and sawdust, the ice lies for months in the dark room, waiting for delivery to neighboring houses and cottages when summer arrives.

In summer, visitors and residents find their way to the Ice House daily. Some come for ice, but they also come seeking bait, ammunition, beer, cigarettes, and newspapers. One chalkboard lists prices for fresh caught fish; another, the prices for vegetables. At dawn, deer can be seen drinking from the lake behind the Ice House before they retreat to refuge on the eponymous mountain. These days, there is almost continuous conversation about the war. Exchanges that in the previous years had been laden with gloom are now lightened by news of allied advances in Europe and the Pacific. Still, some whose husbands or sons have not yet returned avoid any talk of the conflict.

With so many fathers at war, stays in the cottages are short; many of the women work, but because the Knob is less than ten miles from town, a mother might bring her children several times over the course of the summer. A group of women would shepherd a gaggle of energetic kids for a visit. Here they relax, and their children rejoice in exploration and modest adventure.

Older residents of the Knob can usually be found seated along the counter that serves as an informal bar inside of the Ice House. Through the long summer days, the owner sells six-ounce bottles of cream soda, Lithiated Lemon, and Coke, chilled in a tub of icy water. Late in the afternoon, he adds bottles of Dobler beer.

For the kids the Ice House is a great lure, even though the sawdust on the walks and floor grinds into their bare feet. Outside they can cool off on a burlapcovered block of ice, set for delivery. Inside they get to “Shoot the Jap!” at the pinball machine which sits against a back wall.